The last few weeks I've been working on adding an HTTP 1.1 stack to the standard library of Inko as part of this pull request. The work is still ongoing but the initial set of changes will include an HTTP 1.1 server, client, basic cookie handling, generating and parsing of forms, and a request router. This work is based on the following RFCs:

- Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax

- HTTP Semantics

- HTTP/1.1

- HTTP State Management Mechanism

- Returning Values from Forms: multipart/form-data

Unfortunately for me (and others wishing to build an HTTP 1.1 stack), HTTP 1.1 is a rather messy and organically grown protocol rather than something that's well designed. The RFCs reflect that too: they're more like reference documents for how HTTP 1.1 is implemented in the wild rather than an actual specification of how things should be.

The protocol is also full of just plain weird choices. For example, you can send requests and response in chunks using a mechanism known as chunked transfers: instead of sending the data as a whole, you send individual chunks that each start with the size of that chunk. The idea itself isn't the problem here, in fact it's a great idea. What I just can't wrap my head around is the format used for chunk sizes: it's not a sequence of bytes (e.g. a lower-endian integer encoded as individual bytes) or an ASCII decimal number (e.g. 1234). Instead, the chunk size consists of one or more hexadecimal integers. Not decimal, hexadecimal. This means that if your chunk size is 1234 bytes, you encode it as "4D2" not "1234". I guess decimal numbers are too mainstream?

Another fun one is how response lines include the status code and an optional reason string, but a space is still required after the status code if no reason is given. In other words, this is invalid:

HTTP/1.1 200\r\n

Instead it should be this:

HTTP/1.1 200 \r\n

^ Note the space here

As innocent as this may seem, incorrect handling of the status line isn't unheard of.

One aspect of the HTTP protocol that is especially messy is handling of forms and file uploads. Today I want to dive a bit deeper into why that is.

Forms are a boring yet crucial part of pretty much any web application. And yet the way form data is sent as part of an HTTP 1.1 request hasn't changed for at least 25 years (if not longer), and not for the better.

Today there are two "standard" encoding formats used for forms: application/x-www-form-urlencoded and multipart/form-data. You may have noticed that I said "standard" with quotes. That's not a coincidence: while RFC 9110 briefly mentions multipart/form-data, it makes no mention of application/x-www-form-urlencoded. It also doesn't state anything about requiring support for multipart/form-data forms. RFC 9112 makes no mention of either. This means that an HTTP server with no support for either these formats is compliant with the specifications.

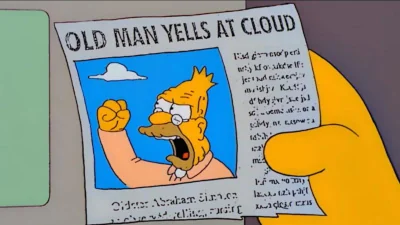

Of course at this point some chronically online smart ass reading this will think to themselves "umm ackchyually, not all HTTP servers need to handle forms ...". While it's true not all HTTP 1.1 servers need to handle forms, the majority of them will have to handle them at some point. As such, a server not able to handle them at all isn't going to be useful to most people out there. More importantly, given how important forms are you'd expect at least some form of guidance on how to deal with them, rather than a brief mention of a single relevant RFC.

So what exactly are these standards anyway? Let's find out.

application/x-www-form-urlencoded

The first and most basic standard also happens to be the least specified. I guess this is on point considering the HTTP 1.1 specification as a whole is rather messy and underspecified in various areas, but I digress.

The data format used is similar to that which is used in URL (or URI, depending on who you talk to) query string components. You know, that string at the end of a URL containing a whole bunch of tracking and referral codes you never asked for:

http://example.com?this-is-the-part-I'm-talking-about

The form format itself doesn't have a specification, instead it seems servers

and clients use the query string grammar rules from RFC RFC 3986.

That is, encoding of a form is done using a sequence of key=value pairs with

each pair separated by a &. If the key of value contains any special

characters that aren't allowed, they are percent/URL encoded as specified in

RFC 3986:

name=Yorick&age=32&country=The%20Netherlands

After publishing this article, I found that this format is briefly defined here in RFC 1866 (which is now obsolete). The WHATWG URL specification defines this format here, but this is a living standard subject to change.

So there are some specifications, but they're not exactly great.

This also highlights the first problem: the lack of a clear specification means different implementations may choose to encode data differently. For example, given a form with the field "key" and the value "😀", different implementations may decide to encode the data differently: some may follow RFC 3986 and URL encode the data where necessary, others may decide to just send the data as-is.

The second problem is that implementations may use different ways of encoding arrays. The two most common ones that I know of are:

- Multiple pairs with the same key name but different values, i.e.

numbers=1&numbers=2 - A single pair where the key name ends with

[]and the value is a comma-separated list, i.e.numbers[]=1,2

A variation of the second approach is to use indexes inside the brackets such as

numbers[0]=1&numbers[1]=2, though I'm not sure how commonly used this approach

is. Either way, the lack of a standard here means different implementations may

end up interpreting the data in different ways, or reject it entirely.

The third problem is that this format isn't suitable for large non-ASCII values such as files uploaded as part of the form, as URL encoding data can increase its size by up to three times (due to URL encoded sequences always requiring three ASCII characters). This means that if your form contains a 10 MiB file to upload, you'd have to (in the worst case) send 30 MiB of data over the wire.

The result is that this format is OK for basic forms containing only a few values, but unsuitable for anything containing large amounts of data such as uploaded files.

multipart/form-data

The second standard is based on a similar format used as part of Emails, and is specified in RFC 7578. Each field and its value is essentially a chunk (or "part") in a stream of fields, consisting of:

- The start of the part

- One or more headers

- An empty line

- The value of the field

The line separator is CRLF (\r\n), similar to HTTP. A form with the fields

name, age and country is encoded as follows:

--BOUNDARY

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="name"

Yorick

--BOUNDARY

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="age"

32

--BOUNDARY

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="country"

The Netherlands

--BOUNDARY--

Suffice to say this format is a bit...odd. For starters, while the boundary

separator must start with -- and (per RFC 2046, which RFC

7578 is based on) must not be longer than 70 characters. The actual

value is arbitrary, and must be specified in the Content-Type header using the

boundary parameter:

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=BOUNDARY

The problem here is that the boundary value may occur in the value of fields, and there's no way of encoding it such that it isn't treated as a separator. As such, the value is typically generated at random in hopes of it not conflicting with any of the values. For example, curl generates boundaries such as this:

--------------------------QTxpn5cdD7OFJs9UQlWEgD--

The second problem is that because the multi-character separator may (partially) occur in the value, parsing this format efficiently is a challenge. It's not impossible, but it's so much more complicated compared to using something sane like oh I don't know, any of the thousands of other serialization formats that exist out there?

At this point you may be wondering: why does that last separator look different?

Shouldn't that be --BOUNDARY instead of --BOUNDARY--. No! You see, using a

distinct closing separator (preferably something that's easy to parse) made too

much sense, so instead we took the format --TEXT and slapped a trailing --

on it and treat that as the final/closing separator (i.e. it signals the end of

the stream). Brilliant!

Which brings us to the headers section, which each part uses to:

- Specify the name of the field and optionally the file name (if relevant)

- Specify the (optional) content-type and encoding of the value

For example:

--BOUNDARY

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="resume"; filename="resume.pdf"

Content-Type: application/pdf

[bunch of bytes]

--BOUNDARY--

Curiously, there's no Content-Length header supported so if you want to read

the value you can't just read N bytes all at once and be done with it, instead

you have to process it in chunks so you don't treat a boundary separator as part

of the value by accident. The use of named headers also further adds to the

bloat of this serialization format. And let's not ignore the fact that the

Content-Type header is as good as useless because there's nothing stopping a

client from lying about the content type of whatever it's sending you ("I

promise this .exe is totally a plain text file").

Oh, and this format still has no notion of arrays, objects or other data types, so good luck getting different systems to agree on how to serialize such data.

The result is that we end up with a way of encoding data that's unnecessarily bloated, difficult to parse efficiently, and hinges on the pinky promise that the boundary separator is random enough such that it doesn't occur within a field's value. Is it the worst format? No, but after almost 30 years you'd expect something better.

So now what?

If you have a form that only needs to upload a file, and you're fine with requiring JavaScript (at least within the context of browsers), then you can do pretty much whatever you want. tus is one alternative protocol for uploading files that I came across, though I haven't worked with it myself or looked into it enough to have an opinion on it.

For forms that mix files and non-files, you're out of luck as browsers only support the two standards mentioned above. In 2014 the W3C made a proposal to use JSON for forms, but work on the proposal stopped in 2015. There are some issues with the proposal (e.g. base64 encoding uploaded files isn't great), but I'd much rather deal with JSON than with application/x-www-form-urlencoded and multipart/form-data.

XForms is also a thing, but to my knowledge more or less nobody uses it and I doubt that will change any time soon.

Possibly the most frustrating aspect is that today we have three competing versions of HTTP, two of which had the benefit of hindsight and one that even comes with its own network protocol. And yet, we're still submitting forms like it's 1985. Grrr...